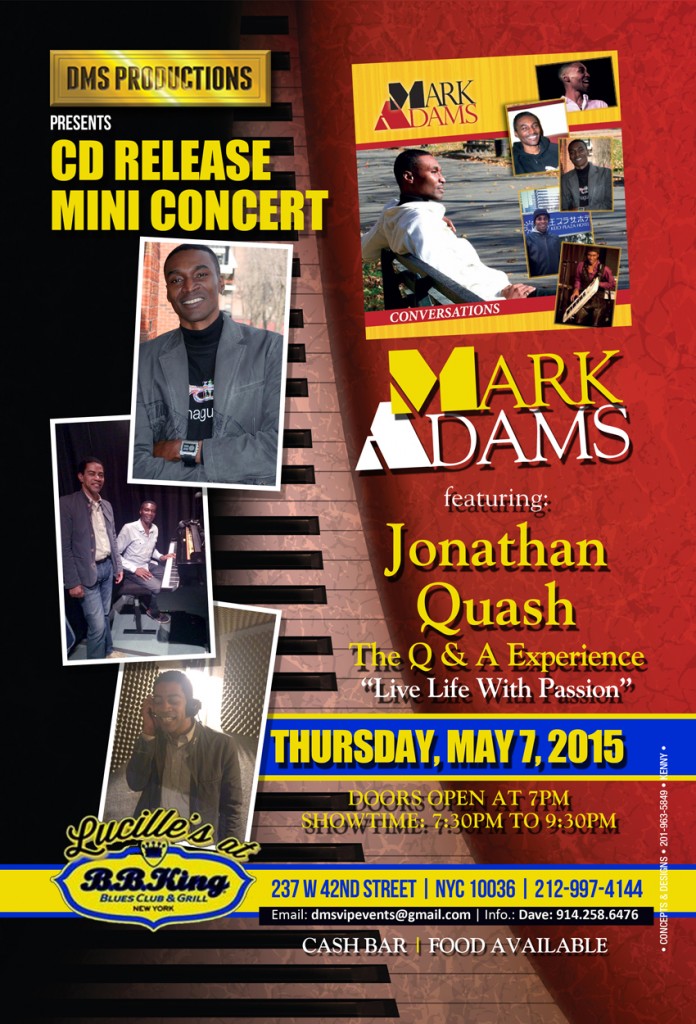

I Forgot To Remember To Forget features guest appearances

by Ron Carter and Roy Ayers

Pianist Mark Adams is learning how to seek out and hold onto the positive aspects of his career and his craft and leave the rest behind. It’s an evolution that we all experience, no matter what our calling in life. But for Adams, the result is better and more artistically satisfying music.

His new album, I Forgot To Remember To Forget, is the latest chapter on that evolutionary journey. It comes at a point in Adams’ career where he has learned how to remember the important lessons that music has taught him and forget the occasional noise he’s encountered along the way. It’s a process of ignoring expectations and preconceptions – either his own or those imposed on him by others – and remaining true to his own creative vision.

“There are certain things that happen in your life that you’re just better off forgetting about,” says Adams, “because they’re irrelevant and counterproductive, and they get in the way of your potential to be the best artist you can be – and the best person you can be. But at the same time, there are certain things you should remember – things that you’re meant to remember because they’re important lessons.”

Adams sets this bit of wisdom to music on the new album with the help of a couple old friends, vibraphonist Roy Ayers and bassist Ron Carter – two seminal jazz figures with whom he has collaborated in the past and whom he counts among his primary mentors. Ayers made his initial mark in the bebop, jazz-funk and R&B of the 1960s and ‘70s. Carter, a member of the Miles Davis Quintet during the 1960s and a prolific sideman and session player in the decades since, is considered the most-recorded jazz bassist in history.

Adams admits that bringing two such titanic figures into the studio for his own project was intimidating, but he was committed to documenting the rare opportunity of working with two legendary figures at the same time and in the same place.

“It’s scary, yes, but it helped raise me to their level of musicianship,” says Adams. “It’s hard to get to their level. They’re from the Miles Davis era, and they’re geniuses of this music. Ron Carter’s presence consumes the room, and Roy Ayers is the same way. Time stops when people like that show up in the studio.”

Time may have stopped, but some great tracks emerged from that timeless moment, thanks in large part to the efforts of Trevor Allen, who produced the album and played bass on a number of tracks. “The production on this record is probably just as important as the songs and the playing,” says Adams. “I trusted Trevor to help me make the best record possible. I trusted everybody. I didn’t feel the need to micromanage anything. It was very liberating.”

“Woke,” the lead-off track, is one of Adams’ favorite compositions in the entire sequence. What started as a simple melody written by Adams became a more collaborative composition with bridges composed by Allen. “Trevor’s parts and my parts together reminded me of something by Pat Metheny,” says Adams, “so I decided to bring in some live horns.” Joe Thomas, who plays the full gamut of woodwinds, developed horn arrangements for the track and brought in trumpeter Joe Porcelli and trombonist Andre Atkins to round out the section.

“Fight the Good Fight” is co-written by Adams and rapper Young Wess, who delivers an unflinching and insightful commentary on the cultural divisions we all struggle with every day. “I encouraged him to talk about some of the things that separate us and keep us from being more connected and more united,” says Adams. “I told him to go with that idea, and be as authentic as he can be. He’s a brilliant rapper, and that brilliance shines through on this track.”

“Blues for DP” is just what the title suggests, a return to the foundation of jazz. “I like this track because it gets back to that basic, straightforward blues structure that’s at the heart of jazz,” says Adams. “A lot of the younger, newer cats won’t play that, because they think it’s too old-school for them. That’s too bad, because you can’t get much more authentic than the blues.”

Adams takes Dave Brubeck’s “In Your Own Sweet Way” in a surprising direction and gives the classic piece a fresh take. “I did it in a harder, funkier way, like a rock song,” he says. “I wrote lyrics for that song, and Jonathan Quarsh does an outstanding job with the vocals.”

Ayers makes his appearance on “Marleigh,” a ballad with a very personal dimension for Adams. “Roy just has a way of understanding where you’re coming from,” he says. “I wrote this song for and about my daughter, but he was able to connect to it and understand the intention behind it. That’s one of the things I’ve always appreciated about him whenever I’ve worked with him. He’s always been able to make the connections with music that you can’t always make with words.”

In addition to composing and performing, Adams is also a lecturer of music at York College, part of the City University of New York. This, perhaps more than any other aspect of his professional profile, is what enables him to recognize the inherent learning experience in the making of I Forgot To Remember To Forget. But the lessons that have come with this project extend well beyond the making of music.

“We’re living in a time of great uncertainty and great anxiety,” he says. “I think there’s something in the title of this album and the concept behind that title that speaks to all of us. We’re only going to be our best selves if we can let go of the things that drag us down and hold onto the things that can make us great as individuals and as a society. I think our future depends on our ability to recognize the difference between what we should remember and what we should forget.”